- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

230,45 €

+ 460 points

Description

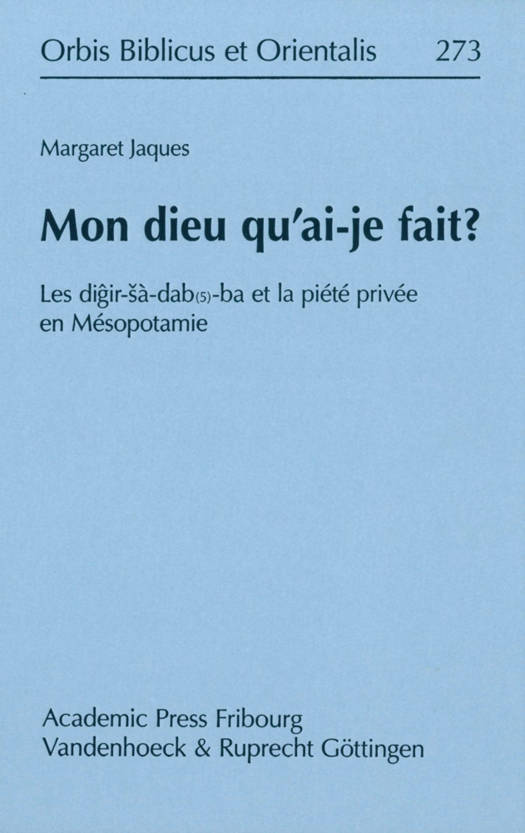

The corpus of penitential prayers to the personal god that bear the signature KA-inim-ma digir a-dab(5)-ba gur-ru-da-kam "Incantation to return the 'tied heart' of the god" gives us an overview of how the inhabitants of Mesopotamia represented to themselves what we would call "private piety". Focusing on this corpus, this book includes texts from the genre's origin in Old Babylonian private devotion up to its use in official Assyrian kings' rituals. The Old Babylonian corpus consists of about 10 tablets in Sumerian that were excavated in various Mesopotamian cities. These tablets include only one prayer, addressed to the personal god. This prayer gives an idea of the wealth of metaphors used to talk about guilt, shame or sorrow. Identical metaphors appear in other similar literary texts and letters. The texts of the Assyrian corpus are either bilinguals (Akkadian and Sumerian) or purely Akkadian. Most of them were discovered in Assurbanipal's library in Niniveh. The Akkadian texts consist of a corpus of prayers in which the Old Babylonian prayer is the fifth one. This prayer derived directly from the ancient Sumerian digir a-dab(5)-ba and was incorporated into official royal rituals, where it took on the character of an "incantation-prayer". The other prayers of the corpus are found in different rituals like Bit rimki, urpu, ama-um-ukin Dream Rituals, and therapeutic texts of the SA.GIG series, magical texts and omen texts. The prayers were first published in 1974, but without the rituals. However, prayers and rituals should be analysed both individually and as a whole, while considering their connections and differences. The corpus of Hittite prayers to the Sun God from 13th century Anatolia, embodies isolated clauses borrowed from the Sumerian digir a-dab(5)-ba. The research published here considers the migration of these sentences from the Sumerian corpus to the Hittite texts, and analyses their use and interpretations in the new context. The Hittite texts are published by Daniel Schwemer in a separate chapter. The whole corpus is important for religious studies. First, it provides insight into private devotion in Mesopotamia, still a very little known topic. Second, the problem of evil is treated, its causes and its deflection or palliation. Naturally, evil is a source of emotions and the way these emotions are expressed in prayers has to be considered in comparison with other kinds of expressions in Mesopotamian culture. Finally, the way a text changes while traveling from one place to another and from one period to another has to be analysed. Study of this corpus illustrates how both historical and synthetic analyses can interact and support each other in order to enhance our understanding of religion in the ancient Near East.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 470

- Langue:

- Français

- Collection :

- Tome:

- n° 273

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9783525544037

- Date de parution :

- 18-01-16

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 160 mm x 237 mm

- Poids :

- 906 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.