- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

56,45 €

+ 112 points

Description

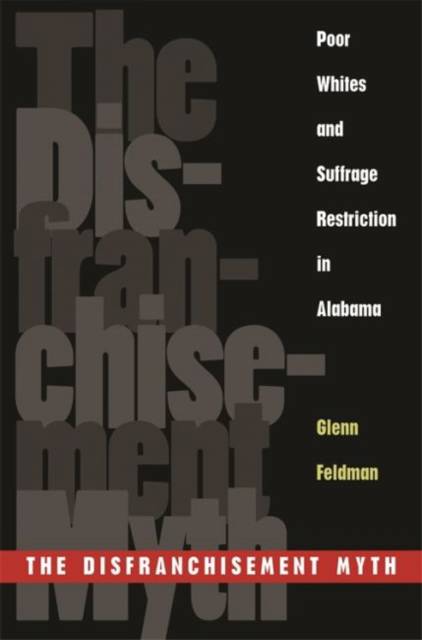

This study challenges decades of scholarship on the roots of disfranchisement in America, arguing that historians have misunderstood the role of race and class in this antidemocratic movement. In 1901 Alabama adopted a new state constitution intended to strip its black citizens of their voting rights. Alabama was not the only state that disfranchised blacks; however, it was the only one where the issue was put to a popular vote by referendum. Glenn Feldman looks anew at the causes and consequences of this landmark event to revise the misleadingly neat view that historians have handed down to us.

Drawing on court documents, voting statistics, civil rights and labor records, and many other sources, Feldman shows that the racist appeals of Alabama's white planters, industrialists, and other conservatives motivated poor whites in far greater numbers and for more complex reasons than received knowledge concedes. The seemingly natural allies of blacks, poor whites constituted most of the white opposition to disfranchisement, says Feldman. Yet the number of poor whites who backed the new constitution was greater. Ultimately, many would be disfranchised by the very measures they had believed were aimed only at blacks. In that sense, says Feldman, poor whites were "more parties to their own demise than the mere victims of circumstance." Such conclusions run counter to those associated with historians J. Morgan Kousser, C. Vann Woodward, and others. Giving new emphasis to race preoccupations where these scholars had focused on class divisions, Feldman reveals the vitally important role that emotion has played in influencing the political behavior of white southerners--often to their profound political and economic detriment. The Disfranchisement Myth has much to say about the tendency of "plain" people in the South--then and now--to allow prejudice and fear to distract them from the pursuit of their rational political interests.Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 328

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780820335100

- Date de parution :

- 15-04-10

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 147 mm x 218 mm

- Poids :

- 430 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.