- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

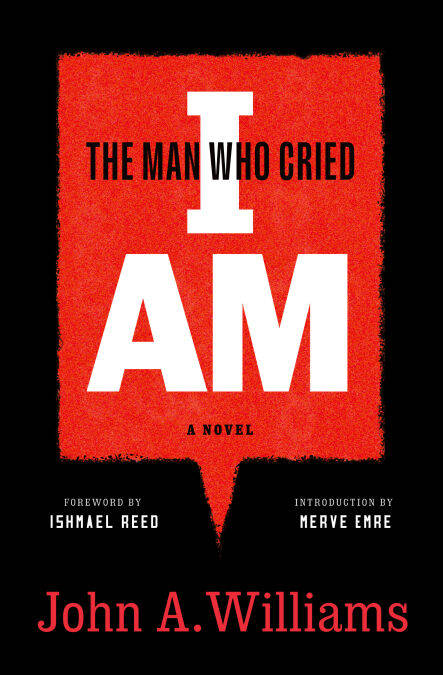

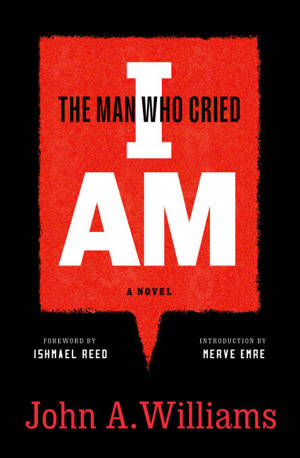

Rediscover the sensational 1967 literary thriller that captures the bitter struggles of postwar Black intellectuals and artists

With a foreword by Ishmael Reed and a new introduction by Merve Emre about how this explosive novel laid bare America's racial fault lines

Max Reddick, a novelist, journalist, and presidential speechwriter, has spent his career struggling against the riptide of race in America. Now terminally ill, he has nothing left to lose. An expat for many years, Max returns to Europe one last time to settle an old debt with his estranged Dutch wife, Margrit, and to attend the Paris funeral of his friend, rival, and mentor Harry Ames, a character loosely modelled on Richard Wright.

In Amsterdam, among Harry’s papers, Max uncovers explosive secret government documents outlining “King Alfred,” a plan to be implemented in the event of widespread racial unrest and aiming “to terminate, once and for all, the Minority threat to the whole of the American society.” Realizing that Harry has been assassinated, Max must risk everything to get the documents to the one man who can help.

Greeted as a masterpiece when it was published in 1967, The Man Who Cried I Am stakes out a range of experience rarely seen in American fiction: from the life of a Black GI to the ferment of postcolonial Africa to an insider’s view of Washington politics in the era of segregation and the Civil Rights Movement, including fictionalized portraits of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. John A. Williams and his lost classic are overdue for rediscovery.

Few novels have so deliberately blurred the boundaries between fiction and reality as The Man Who Cried I Am (1967), and many of its early readers assumed the King Alfred plan was real. In her introduction, Merve Emre examines the gonzo marketing plan behind the novel that fueled this confusion and prompted an FBI investigation. This deluxe paperback also includes a new foreword by novelist Ishmael Reed.

“It is a blockbuster, a hydrogen bomb . . . . This is a book white people are not ready to read yet, neither are most black people who read. But [it] is the milestone produced since Native Son. Besides which, and where I should begin, it is a damn beautifully written book.” —Chester Himes

“Magnificent . . . obviously in the Baldwin and Ellison class.” —John Fowles

“If The Man Who Cried I Am were a painting it would be done by Brueghel or Bosch. The madness and the dance is never-ending display of humanity trying to creep past inevitable Fate.” —Walter Mosely

With a foreword by Ishmael Reed and a new introduction by Merve Emre about how this explosive novel laid bare America's racial fault lines

Max Reddick, a novelist, journalist, and presidential speechwriter, has spent his career struggling against the riptide of race in America. Now terminally ill, he has nothing left to lose. An expat for many years, Max returns to Europe one last time to settle an old debt with his estranged Dutch wife, Margrit, and to attend the Paris funeral of his friend, rival, and mentor Harry Ames, a character loosely modelled on Richard Wright.

In Amsterdam, among Harry’s papers, Max uncovers explosive secret government documents outlining “King Alfred,” a plan to be implemented in the event of widespread racial unrest and aiming “to terminate, once and for all, the Minority threat to the whole of the American society.” Realizing that Harry has been assassinated, Max must risk everything to get the documents to the one man who can help.

Greeted as a masterpiece when it was published in 1967, The Man Who Cried I Am stakes out a range of experience rarely seen in American fiction: from the life of a Black GI to the ferment of postcolonial Africa to an insider’s view of Washington politics in the era of segregation and the Civil Rights Movement, including fictionalized portraits of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. John A. Williams and his lost classic are overdue for rediscovery.

Few novels have so deliberately blurred the boundaries between fiction and reality as The Man Who Cried I Am (1967), and many of its early readers assumed the King Alfred plan was real. In her introduction, Merve Emre examines the gonzo marketing plan behind the novel that fueled this confusion and prompted an FBI investigation. This deluxe paperback also includes a new foreword by novelist Ishmael Reed.

“It is a blockbuster, a hydrogen bomb . . . . This is a book white people are not ready to read yet, neither are most black people who read. But [it] is the milestone produced since Native Son. Besides which, and where I should begin, it is a damn beautifully written book.” —Chester Himes

“Magnificent . . . obviously in the Baldwin and Ellison class.” —John Fowles

“If The Man Who Cried I Am were a painting it would be done by Brueghel or Bosch. The madness and the dance is never-ending display of humanity trying to creep past inevitable Fate.” —Walter Mosely

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 500

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781598537628

- Date de parution :

- 20-11-23

- Format:

- Ebook

- Protection digitale:

- Adobe DRM

- Format numérique:

- ePub

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.