- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

43,45 €

+ 86 points

Description

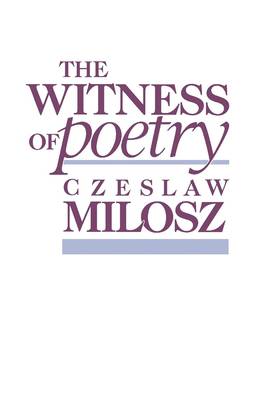

"A classic for our time."--Saturday Review

The Nobel Prize-winning writer on poetry as testimony to the upheavals of the twentieth century. For many years, Polish émigré Czeslaw Milosz's poetry was relatively unknown outside of Eastern Europe. While his 1953 anticommunist tract The Captive Mind had solidified his reputation as a political thinker in the West, his poems languished in obscurity, distributed mostly by underground Polish presses evading censorship from the communist regime. Only once he won the Nobel Prize in 1980 did his unique poetic voice--prophetic, ironic, sometimes bitter, but always hopeful--gain wider recognition, from both English-speaking audiences and the Polish government itself, which could no longer suppress the brilliant, irascible defector. Collecting Milosz's 1981-1982 Norton Lectures, The Witness of Poetry offers an unparalleled window into this heady moment in his career. Newly recognized as one of the great poets of his time, Milosz stages an ambitious defense of the need for poetry amid the ruins of a catastrophic twentieth century. Rather than reacting to the procession of world wars and totalitarian regimes by fleeing from reality into abstruse symbolism or "pure poetry," Milosz argues that poetry must be "a passionate pursuit of the real." Only then will poets liberate themselves from the cramped confines of a bohemian subculture and rejoin the "great human family." And only then will poetry become "as essential as bread." Introducing Western audiences to a wide range of Polish voices, from Adam Mickiewicz and Wislawa Szymborska to Oscar Milosz, his distant cousin, Milosz's lectures vividly reveal that Polish poetry remains a wellspring of "incorrigible hope," not despite but because of Poland's calamitous history.Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 128

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

- Tome:

- n° 38

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780674953833

- Date de parution :

- 01-01-84

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 154 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 195 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.