- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

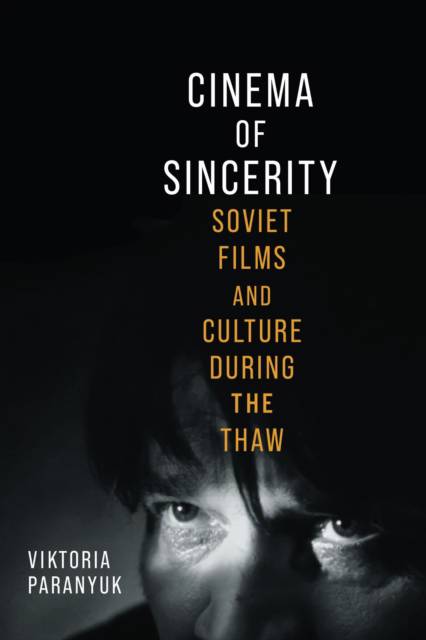

Following Stalin's death in 1953 and Khrushchev's acknowledgment of Stalin's crimes in 1956, "sincerity" emerged as a cultural imperative in the Soviet Union. The cinema of this period turned inward, insisting on ordinary characters and creating a sense of spontaneity through particular staging methods and cinematic techniques, such as interior monologue and the close-up. These changes shifted the understanding of what "realism" meant and allowed Soviet cinema to reestablish with its audiences the trust that had been corrupted by serving Stalin's cult of personality. Using both theory and close readings of specific films produced in the Soviet Union during the Thaw, a period known for its relative political and cultural liberalization, Cinema of Sincerity treats sincerity as both a concept and an aesthetic strategy. Viktoria Paranyuk argues that Soviet cinema's use of sincerity was a reworking of a trend in global cinema that sought to bridge the gap between reality and the filmed image. This period saw increased accessibility to world cinematic traditions, new voices in criticism, and, above all, the multigenerational effort in filmmaking that developed and thrived in centers outside Moscow. Paranyuk demonstrates how these changes allowed Soviet cinema to renew its visual language and use film as a space for collective self-examination.

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 256

- Langue:

- Anglais

- Collection :

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9780299354602

- Date de parution :

- 16-12-25

- Format:

- Livre relié

- Format numérique:

- Genaaid

- Dimensions :

- 152 mm x 229 mm

- Poids :

- 453 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.