- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

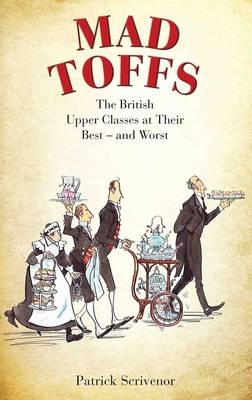

Mad Toffs

The British Upper Classes at Their Best and Worst

Patrick Scrivenor

Livre broché | Anglais

13,95 €

+ 27 points

Description

This record shows the British upper classes--and a few others--displaying a sort of unhinged blitheness of manner that leads them to say and do strangely unexpected things. It is a quality of innocent insolence, or maybe guileless arrogance, which belongs only to the very rich, the very privileged and the very idle. Consider Lord Hartington, son and heir of the seventh Duke of Devonshire, who contrived to shoot dead a pheasant flying low through a gate and the retriever that was pursuing it, while also peppering (a) the retriever's owner, and (b) the chef from Chatsworth House. When asked if he regretted taking this risky shot, Hartington replied, "Well of course. If I had killed Chef we'd have had no dinner." Or the first Earl of Durham who, in the early 19th century, remarked that "GBP40,000 a year is a moderate income--such as one man might jog along with." He was not speaking from experience, his own annual income being a healthy GBP80,000 a year at the time--or between GBP6 million and GBP8 million in today's money. Or the third Duke of Buckingham and Chandos, to whom it was tentatively suggested by his advisers that perhaps employing six chefs was excessive, and one, the pastry cook, might possibly be dispensed with, as an economy. The Duke gazed bleakly at his straitened future. "Can't a chap have a biscuit?" he complained. Patrick Scrivenor has combed the annals of the British aristocracy to provide an illuminating←and wildly funny--portrait of people who, though often talented in their own fields, courteous and well-meaning, generous and even liberal-minded, none the less display a certain disconnectedness from the realities that tend to afflict the less elevated echelons of society. The result is clear evidence that what many call "eccentricity," the more rational would probably describe as "plain bonkers."

Spécifications

Parties prenantes

- Auteur(s) :

- Editeur:

Contenu

- Nombre de pages :

- 288

- Langue:

- Anglais

Caractéristiques

- EAN:

- 9781784187675

- Date de parution :

- 01-01-17

- Format:

- Livre broché

- Format numérique:

- Trade paperback (VS)

- Dimensions :

- 127 mm x 203 mm

- Poids :

- 314 g

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.