- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

- Retrait gratuit dans votre magasin Club

- 7.000.0000 titres dans notre catalogue

- Payer en toute sécurité

- Toujours un magasin près de chez vous

Description

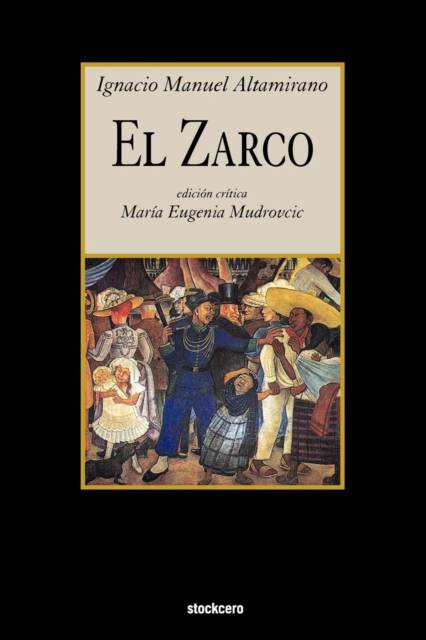

El Zarco by Ignacio Atamirano in a US printed edition with preliminary study and notes by Maria Eugenia Mudrovcic Ignacio Manuel Altamirano's posthumous novel, El Zarco (1901), is much more than a novel about bandits. Written amidst the «pax porfiriana», at the height of Altamirano's reputation within the cultural elite, the novel is a narrative that deals with the chaos and the banditry that prevailed in the 1860s to celebrate the insertion of Mexico into the international markets undertaken by Porfirio Díaz. Considered to be «the first Mexican novel» because of its carefully constructed structure, El Zarco is also "original" in its approach to race: green-eyed white characters are the villains, while the heroes are Indian or mestizos. What makes a heroe, however, is not a matter of race, but the strict adherence to honor, family and hard work, the «civil» values guiding the actions and the ethos of each and every good citizen or "hombre de bien" of Yautepec. The nineteenth century bourgeois obsession with "crime" emerges in El Zarco as the matrix of the two stories that end up being one: "crime" is the cause for the fear and «insecurity» that paralyze Yautepec middle classes as well as the reason for the glorification of the rural police. Altamirano presents the «good love» between Nicolas and Pilar as a counternarrative of the sexually undisciplined story of lust enacted by Manuela and el Zarco. But this narrative line seems to be, nonetheless, only a frame to celebrate Sanchez Chagollan as the heroic founding father of the police created by Benito Juárez in 1861 that later became an icon of the institutional order of the Diaz regime. In the study that introduces this edition, Maria Eugenia Mudrovcic reads the «unorthodoxies» of Altamirano's novel as part of the propaganda apparatus set by Porfirio Diaz in his effort to change the image of Mexico as a «bandit nation» that dominated the press at the time. Why Altamirano talks of «violence» in «times of peace», thus, becomes the starting-point for a reading of El Zarco that pays attention not so much to bandits but rather to the police that was created as the only way to combat them.

Les avis

Nous publions uniquement les avis qui respectent les conditions requises. Consultez nos conditions pour les avis.